JAWS at 50: the Big Bang of John Williams' career

A trip to the launchpad where John's rocket truly blasted off.

On June 21, 1973, The Hollywood Reporter announced that “Steve Spielberg” would be directing a film adaptation of the soon-to-be smash hit book, Jaws. This news was made before Spielberg’s feature debut, The Sugarland Express, had even premiered, so most people didn’t know who “Steve” was. But John Williams did. He had met the cinematic whiz kid six months prior, and by now had already seen just what a wizard of a director he was; in fact that same month—June 1973—was the month John recorded his first score for a Spielberg film.

And while The Sugarland Express is a little gem, a delightful road movie with astounding command behind the camera and a twangy, tasty score with a fabulous main theme for harmonica, it didn’t really make a splash in popular culture—and was quickly forgotten. Not only that: John and Spielberg’s debut as an artistic duo was unassuming, small, and not at all indicative of the grand, old-fashioned, Romantic moviemaking and movie-scoring they would become known for.

It was Jaws, which turns 50 this Friday, that became their explosive introduction to the world. And even though John had been toiling and doing great work for some 20 years leading up to this moment, increasingly earning accolades and better assignments, Jaws was the Big Bang of his career. Few people knew who he was before June 20, 1975… and then everybody knew who he was.

What new is there to say about Jaws, really? It was the biggest hit of all time when it came out, a cultural phenomenon, a marketing bonanza, an instant zeitgeist that never really went away. The tale of its difficult and crazy production has been dissected and recounted in books and documentaries; a new one is coming out on July 10 from our friend Laurent Bouzereau (director of Music by John Williams). John’s score is one of his most beloved and best known—the central motif is maybe the most famous unit of music ever conceived by a human being—and it has been hummed, performed, and parodied ad nauseam for the past fifty years.

It’s easy to take it all for granted.

But I’ve learned that few people know much about John Williams ante-Jaws, if anything. It’s almost like he just leapt into the cultural stratosphere in 1975 ex nihilo. In my book this pre-Jaws era constitutes some 160 pages, which I feel carries a large slice of the book’s worth.

Let us just briefly go back in time, back to those early weeks of June 1975 and to what John’s life and career were just before the Summer of Jaws.

Here’s a snapshot: he was 43 years old, recently (and very suddenly) widowed, raising three teenage children by himself. His home and emotional life were pretty devastated. Professionally, he had now been a steadily working musician—recording artist, sideman, film and TV composer, and a budding concert composer and conductor—for nearly two full decades. Early on he had failed to make it as a marquee jazz artist and found sturdier success scoring movies and episodic television. But a lot of the work he was assigned throughout the 1960s was either disposable or downright trash, and even his clever and often beautiful writing largely went into the cultural dustbin along with it.

In his prolific scoring career prior to June 1975, John had scored corny TV shows (some of them beloved by kids of that generation), creaky dramas, juvenile sex comedies, and quite simply a lot of mid cinema. John’s trusty orchestrator, Herbert Spencer, reflected that John’s music was always “very up-town,” and “here he gets these lousy pictures and he writes this kind of stuff. But he was just trying to get his nails into something. ... Since he never really had a real good picture to work on, you couldn’t really tell what he could do.”

By that decade’s end he was finally able to strut his stuff as an old-school film symphonist and brilliant melodist in scores like Heidi (1968) and The Reivers (1969), and he had also been promoted to lavishly arranging and orchestrating big movie musicals like Goodbye, Mr. Chips and Fiddler on the Roof—the latter garnering his first Academy Award. As of the early ’70s he had arrived at a certain level of artistic cachet and was working with auteurs like Robert Altman and Martin Ritt, and he earned some positive attention from critics with his experimental scores for The Long Goodbye and Images. He was also playing to his biggest audiences yet as composer for the uber-popular disaster genre—The Poseidon Adventure, The Towering Inferno—which Jaws was lumped in with before it came out.

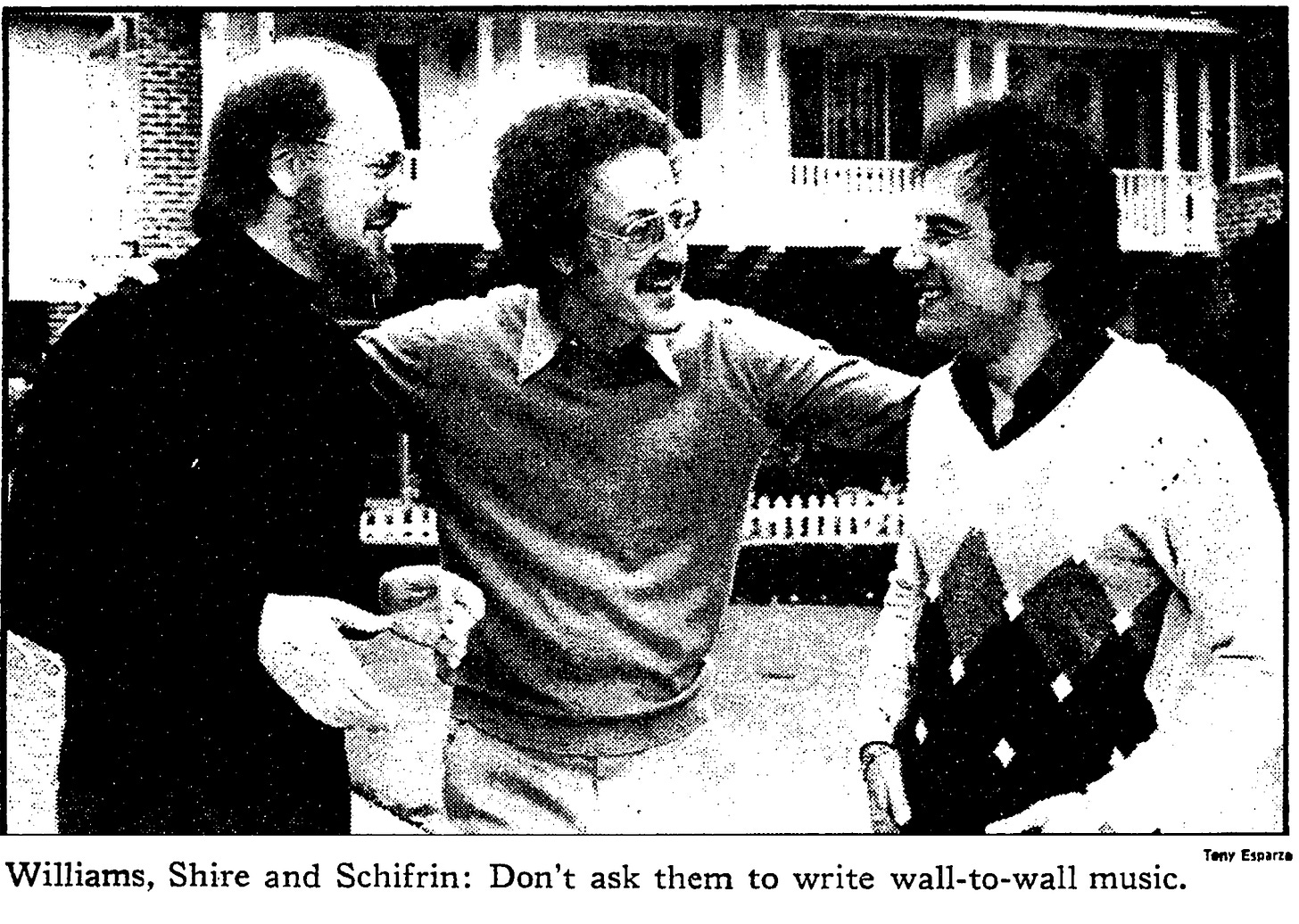

So he was on a launchpad, his engines roaring, and in hindsight it all looks somewhat inevitable. But, I would argue that if he had not been courted by this young, slightly square wunderkind who had very unhip and out-of-date tastes in movie scoring, and had Spielberg not brilliantly made this taut, charming, and operatic sea adventure, John’s career might never have really skyrocketed. If you look at his contemporaries—Jerry Goldsmith, Lalo Schifrin, David Shire—a lot of them scored hit films and worked with popular directors, but none of them became the household name and had the epic trajectory that John had.

Was John simply more talented? Some would say yes—but the cold fact is, as a film composer your career is hugely dependent on luck and the talent (and success) of the directors you partner up with. John didn’t even go looking for Spielberg; Spielberg came to him. And Spielberg was an anomaly, not just as a preternatural master of film language, but as someone who wanted his movies scored like Alfred Newman and Miklós Rózsa and Dimitri Tiomkin had scored the movies he loved as a kid. His contemporaries were breaking away from the ancient ways of symphonic orchestras and hummable themes, leaning much more toward spare, experimental, or band-like music or just outright dropping the needle on existing rock or classical tracks. Grandiose, storytelling, capital-m Movie Music was going extinct.

“The last great old-style score before John was Spartacus in 1960,” Spielberg once said, “a film that represented the end of an era in several respects. Elliptical films, vignette films became popular, and the big entertainments that the movies had created to compete with television were over. I had to stop buying movie soundtrack albums because there weren’t any I wanted to hear anymore!”

It was downright weird that this nerdy director marvel in his 20s wanted to team up with this seasoned jazzbo-slash-classical composer in his 40s and asked John to write scores like they did back in the ’30s.

But that’s exactly what happened, and so John Williams defied the vogue—and even defied Spielberg’s preconceptions (the director famously temped Jaws with John’s atonal nuthouse score for Images)—and because the canvas of this movie could handle it, and because he was now a veteran of his craft with a lot of music and mileage behind him, it was like a match striking a gas-soaked matchbook.

Spielberg wanted some ancient film music magic, and John was raring to deliver it. The result was a kinetic, infectious, terrifying, thrilling, adventuresome masterpiece that made the movie incandescent, and that also levitated well above the unconscious background normally reserved for film scores and shot directly into audience’s ears and hearts.

This incredible alchemy, a potion from another era, is what really ignited John’s (and Spielberg’s) extraordinary career. It directly led to Star Wars and to John’s long reign at the top of the box office. It was the opening salvo to John’s vocation as a conductor, because now he had written music that a wide audience wanted to hear at an orchestra concert. It was the moment he became a celebrity, as opposed to an anonymous “below the line” craftsman (like most film composers usually are). It was the moment he arrived.

By September 1975, the theme made it onto the Billboard Hot 100, and the following March the score won a Grammy, a BAFTA, and John’s first Oscar for Original Score. (In his acceptance speech video above, he actually hopped onto the stage from the orchestra pit because he was that evening’s music director.)

There is Before Jaws and there is After Jaws. John’s career became a white-hot supernova from this point on—and in a way it never cooled down.

Jaws was the first movie he scored that spawned sequels (he scored Jaws 2 but not any others), the first modern blockbuster, and really the first time he was a prominent feature in a piece of populist mass entertainment for all ages.

Jaws made John Williams; John Williams made Steven Spielberg (to a large degree); and Steven Spielberg (and his pal George Lucas) made the pop culture zeitgeist, globally, from the 1970s through the 1990s, with massive reverberations to this day.

Alfred Hitchcock saw Jaws and decided he wanted to work with John on his next—and what would be his last—film, Family Plot. Stephen Sondheim took inspiration from the Jaws score when he wrote Sweeney Todd. The great Jerry Goldsmith, who was nominated in the same category at that year’s Academy Awards, later said it was the only score he didn’t mind losing to: “For me it is one of the first scores with a personality. I believe in that idea: that music have a point of view, a character point of view. It’s very apparent what he did, but damn it, it worked. It’s the only time I ever lost an Academy Award that I didn’t mind. The Wind and the Lion was a good score, but that was not a heartbreak year.”

And Jaws made John Williams essential. He was no longer “below the line,” a post-production routine, an afterthought. A few years later, producer David Brown said: “We find out first if we can get Williams for a movie before we assign a writer or look at actors.” Spielberg couldn’t conceive of working without him, and other directors scurried into line to implore his Midas touch.

Sure, to some people it was just a silly popcorn movie about a man-eating shark, with a “simple” “two-note” theme. But really… it was the beginning of an epoch.

Event announcement!

For anyone in the Los Angeles area, I’ll be co-presenting a talk on the Jaws score at the Hollywood Bowl ahead of the LA Phil’s live-to-picture concert on Saturday, July 5. Come say hi!

Also: watch this space for news about a fun Jaws 2 happening in November. 🦈

https://www.hollywoodbowl.com/events/performances/3586/2025-07-05/jaws-in-concert-with-the-la-phil

Be careful when opting for tickets in the "Pool Circle"!

I can’t wait to read the full account. (And how well I remember the JAWS / John Williams phenomenon. It was one of the first soundtracks I wore out.)