John Williams and Jerry Goldsmith

Two titans... arguably the best to ever do it... who were like brothers... and all that that implies

“Everyone was looking to see who was gonna win the race, to become the number one composer in Hollywood. And Goldsmith was very talented. But of course John finally won out.” —Tommy Morgan, harmonica player

John Williams celebrated his birthday on Sunday (February 8). Today, February 10, is Jerry Goldsmith’s birthday.

They were born only two days and three years apart, but Jerry (born in 1929) sadly left us more than 20 years ago, claimed by cancer at age 75. Somehow, miraculously, John just turned 94, and did so amidst finishing up recording the score for his 110th feature film—Disclosure Day—and his 30th for Steven Spielberg. Life is certainly strange.

You all know that I hold John Williams in the highest esteem possible, but if I had to name my second favorite composer it would be Jerrald King Goldsmith. I came to him much later than John… mostly because he wasn’t scoring movies I was allowed or drawn to watch as a kid (I also just wasn’t paying as keen attention to the ones I did see). My first eureka moment with Jerry was Air Force One in 1997, arguably a lesser/later effort that nonetheless was so melodically and emotionally potent that it put him on my radar and made me go back and explore his (voluminous) other work already in our family library. Rudy. Poltergeist. Hoosiers, Mulan.

Holy cow—this guy was phenomenal.

He had John’s melodic gift, an equal versatility, a genius for dramaturgy and psychology; he was also more experimental in his orchestration and eager embrace of electronics. A lot of his movies were reputably (and truly) bad. But it didn’t matter: I fell in love listening to the soundtrack albums—for Legend, for Under Fire, for The Final Conflict, I.Q., The Shadow, Islands in the Stream, Twilight Zone: The Movie, The Russia House…

Here was a prolific, insanely talented film composer whose music spoke to my soul much the same way that John’s did. The major difference, besides a quantifiably different writing voice, was that Jerry never had a Steven Spielberg, never had the fortune of a hot streak of beloved and culturally significant films to his name. To be sure, there were box office hits (Alien, Gremlins) and critically lauded features (Chinatown, Patton) along the way—but on the whole, Jerry was attached to a fleet of sinking ships and stinkers. So I did not, with a few exceptions, have the advantage of also loving the stories and images and characters attached to his masterful music.

They were like brothers… Jerry the older and more experienced, John the younger and yet much more successful and popular. Jerry, born and raised in Hollywood and inspired to score films from the time he was 14. John, brought to Hollywood by his dad at age 15, never really interested in movies or film scoring and yet orbiting that destiny from childhood and aware of its potential for steady work and (possibly) creative expression. (Fun fact: when young John was still living in Flushing, New York, in the 1940s, they lived next door to a family named Goldsmith.)

Jerry got his start composing for radio and live television; John got his start playing session piano. One of John’s earliest gigs was on a Goldsmith score: City of Fear. Tommy Morgan, the late harmonica player, remembered another session that took place a few years later, for Studs Lonigan: “There was a tremendous piano solo, kind of ragtime. And John was a great sight reader, and a grand piano player. … Jerry and John were the two hot new composers in Hollywood at that time. And so Jerry announced it and how great John was, and that John had reluctantly agreed to play for him. The score featured a lot of piano solos, and brilliantly played.”

They were in each other’s company from the very beginning, and a natural attraction—and friendly competition—resulted. They were both on staff at Revue scoring weekly television, “all trying to outdo each other and do something unique and different,” Goldsmith said. “We took such pride in it and it was really very exciting, and we’d all listen to each other … There was a friendly camaraderie at the same time.”

In the 1960s, Jerry firmly had the upper hand. He was working with talented auteurs and getting plum assignments: social dramas like A Patch of Blue starring Sidney Poitier, avant-garde thrillers like John Frankenheimer’s Seconds, and pop culture phenomenons like Planet of the Apes. The material was strong and the canvases wide open, and Jerry’s penchant for experimenting with modernism and daring orchestration was consistently rewarded. Meanwhile, John was stuck with cornball TV shows and puerile sex comedies, trapped in a light stylistic box and nothing rich to work with.

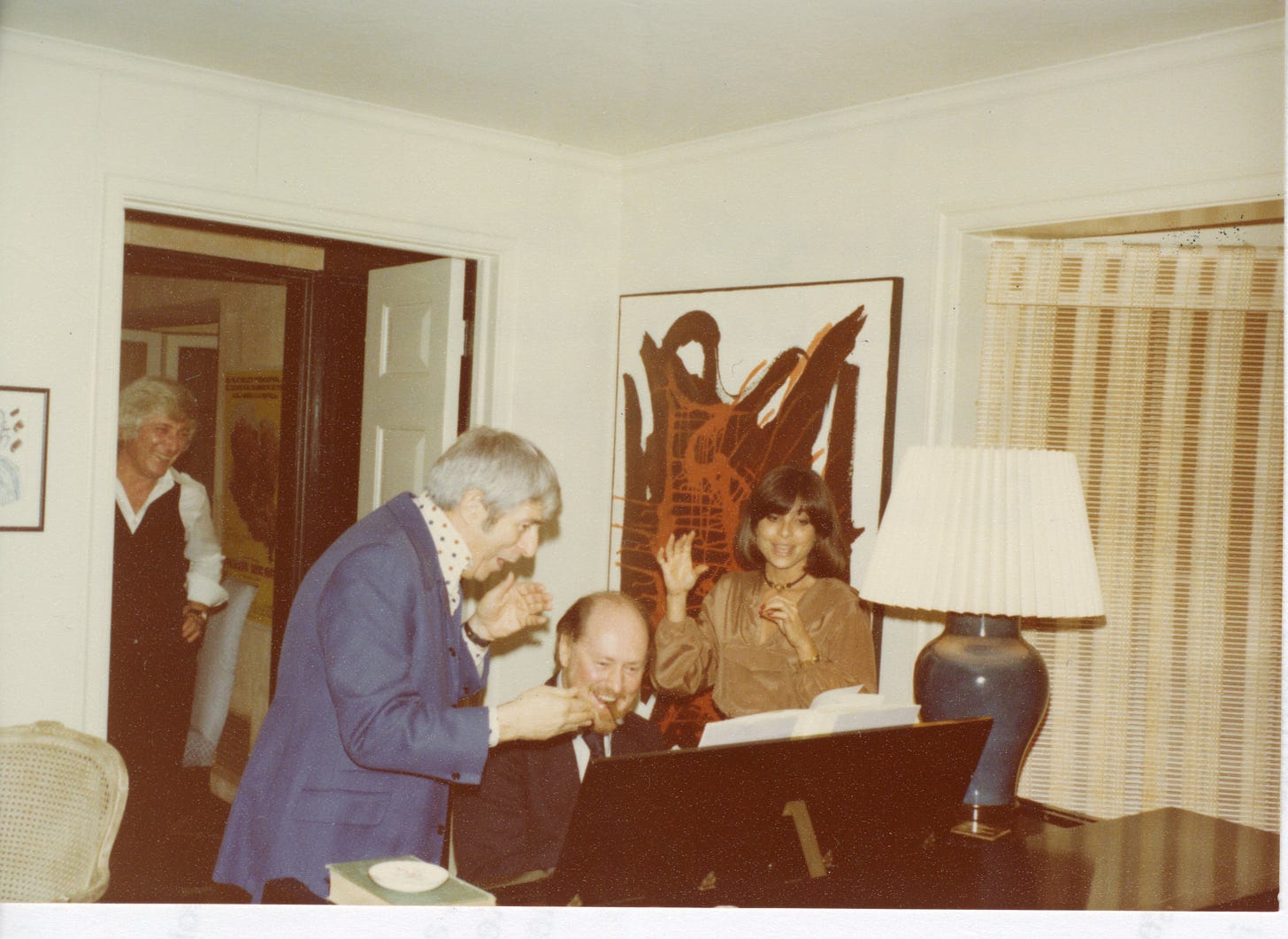

John and Jerry were genuine friends. I’ve heard stories of cocktail parties where they would play four-hand piano together, and I have photos both of John and Barbara with Jerry and his first wife, Sharon, as well as photos of John and Samantha with Jerry and his second wife, Carol. Alex North’s son, Steven, remembers parties at his house where “John and André Previn and Jerry Goldsmith, and various other composer types, would come over and play, sometimes four hands, sometimes eight hands, on the two grand pianos that were in the living room. And they would do everything from show tunes to Schumann and Schubert. It was extraordinary. They would consume certain amounts of alcohol, and the evening would go on, and the playing, starting after dinner at about nine o’clock, would go on until 1 or 2 or 3 in the morning—along with very, very passionate political discussions.”

Their lives intertwined in other ways. John’s kids went to Oakwood School in North Hollywood, where a bunch of other children of Hollywood industry folks went—including Jerry’s daughters. They worked on the Fox lot together, kibitzing over cigars and spirits with their mutual pal, Lionel Newman (pictured above) and eating lunch at the commissary.

When I mentioned Jerry’s name in one of my interviews with John, he responded:

Wonderful composer.

Were you close?

Pretty close. Pretty close.

Was there an element of competition there, since you were both kind of writing scores at the same time?

Yes, I suppose. But we were never on equal par, you know—he was always ahead of me with the assignments he did. Wonderful composer. And I used to play piano for him quite a bit. … I liked Jerry very much. We had a lot of laughs. We had nicknames for each other. Do I want to tell you what they were?

I know Lionel’s nickname for Jerry...

Gorgeous?

Yeah.

[Laughs] Yeah. Great. Well, we’ll leave it there.

By the 1970s John began to catch up with Jerry in terms of choice assignments and industry recognition. At the 1974 Academy Awards, Jerry was up for Papillon and John for Cinderella Liberty; the next year John was nominated for The Towering Inferno, Jerry for Chinatown. (Both Goldsmith movies far superior to the Williams movies—a dynamic that would soon get flipped.) When John won his first Oscar for best score in 1976, beating Jerry’s score for The Wind and the Lion, Jerry said it was the one time it didn’t bother him to lose. “For me [Jaws] is one of the first scores with a personality,” he told the Los Angeles Reader in 1986. “I believe in that idea: that music have a point of view, a character point of view. It’s very apparent what he did, but damn it, it worked. It’s the only time I ever lost an Academy Award that I didn’t mind. The Wind and the Lion was a good score but that was not a heartbreak year.”

Meanwhile, that very year he won his Oscar for Jaws, John told an interviewer: “I always think of Jerry Goldsmith as one of the best composers working in the film medium.”

This was a critical moment, and John and Jerry were seen as leaders in the new wave of Hollywood composers helping revive the art of film scoring. They were both profiled by the New York Times in 1975 (“Goldsmith is probably the most accomplished of this group,” the Times reporter wrote) and again in 1976: “Men like Lalo Schifrin, Jerry Goldsmith, John Williams, David Shire and Billy Goldenberg exemplify a talented breed of Hollywood composer, resourceful and often inventive in their solutions to musical problems that come up in movies.”

The moment was critical, too, in that John’s rocket to global fame and unparalleled success and opportunity was taking off… just as Jerry’s luck was beginning to turn southward. John has often been credited for reviving the symphony orchestra and the classical Hollywood score, thanks primarily to Star Wars in 1977. But we should never forget that Jerry Goldsmith was also writing for orchestra, also bringing a neoclassical / operatic approach to movies. His outstanding work in the ’70s includes a dreamy, melancholy tone poem for Islands in the Stream (starring George C. Scott as Ernest Hemingway), a haunting fantasy for harmonica and orchestra in Magic (starring Anthony Hopkins as a loony ventriloquist), and one of his crowning achievements: The Omen, a satanic mass that is equally disturbing and tenderly beautiful.

Of course, Jerry was also incorporating synthesizers and often writing for wildly unconventional ensembles. “Jerry’s orchestration was Jerry’s entirely,” John told me. “He’d have one flute and one electric saw and whatever [laughs]. They were very ingenious and personal.” The two composers were very different in this regard, and John even expressed some frustration about it to me; it made Jerry’s music difficult to ever program in concert.

Jerry had his big moment in March 1977: he won his first Oscar, justly, for The Omen. But it was the last time he could claim any kind of victory in this competition. Two months later came Star Wars… and Jerry would be eating John’s dust (and leftovers) for the rest of his career.

“I loved Jerry,” John told me. “We were good friends, even before I was a composer so to speak.” But, he said, “Jerry was... not a happy man. And I can’t really tell you why. He was always bothered by certain things—many of which I don’t know anything about.”

To be continued…

Great read, and looking forward part 2! I enjoy Goldsmith’s score to Supergirl, but particularly because he was originally slated to compose the score to Superman. So you can hear what his Superman theme might’ve* sounded like, although I’m sure his main theme to Supergirl was at least partly inspired by Williams. It definitely sounds like a “cousin” of Williams’s theme, as Supergirl is indeed Superman’s cousin.

Wonderfull. Your next book has to be about Jerry Goldsmith biography!!