Johnny Williams, session player

A tour of the Hollywood scoring stages where John Williams cut his teeth as a workaday pianist at the outset of his career.

John Williams insists he never intended to be a film composer—that he fell into it sideways, as if by accident. There’s certainly some truth to this; as a teenager what he really wanted to be was a concert pianist, and he put in Olympian efforts to that end.

But when you look at his path in hindsight, John seemed predestined to score movies—starting with his father’s show business and film music orchestra career, through to young John jamming with and being taught by musicians who worked for the big studios. And his destiny truly becomes apparent when you consider his first steady professional work: as a session piano player on hundreds of movies and TV shows.

He’s often spoken about this period of his life, about what a valuable education it was for him to play with an orchestra for the first time, on a daily basis, and to observe the old masters at work—Alfred Newman, Dimitri Tiomkin, Franz Waxman—and soak up the mechanics and vernacular of Hollywood cueing and scoring, the hallmarks of each genre, and how to run a session and communicate with players. He’s talked about the “temerity of youth” he possessed to then agree to orchestrate cues for these composers, and how, slowly, inevitably, he wound up scoring TV and movies himself.

But there’s been a lot of mystery (and misinformation) about this chapter in his life, and for my book I wanted to sift fact from fiction, solve outstanding riddles, and try and draw as complete a portrait of his session career as possible. Did John actually play the gorgeous piano solos in the score for To Kill a Mockingbird, as I’d been telling my students at USC for years? Did he play on Breakfast at Tiffany’s? Which Bernard Herrmann scores did he play on? How long was he on the staff orchestra at Columbia Pictures? Just which, and how many, iconic film scores did he play on?

This, along with his genealogy and pre-fame history, was one of the more daunting archeological digs I attempted.

The central site for this dig was the American Federation of Musicians Local 47. Over the years I had requested “Studio Orchestra Manager’s Reports” (OMRs) from the AFM for various research projects; these are the official records the union kept of who played what instrument on every film or TV scoring session here in town, and they also include the session dates and recording location. They are very cool artifacts and roadmaps; when, for instance, I wanted to find out who played the wacky synthesizer parts on John’s score for Heartbeeps, I requested the OMR for that title (which led to a very fun interview with Nyle Steiner).

These were the receipts I needed.

But I very quickly learned that I couldn’t just ask for “all OMRs that list John Williams playing piano.” Most of these reports have not been scanned and digitized, and they are not searchable by musician’s name. They’re stored in filing cabinets, and organized by film/production company.

In short: it’s a gigantic haystack that isn’t catalogued by the names of needles.

To top it all off, Local 47 does not let outside researchers inside these vaults anymore; many years ago, when their doors were wide open, they had too many opportunists and bandits sneak off with cool mementos that wound up on eBay or just in people’s personal collections. So I couldn’t even do this laborious, time-intensive trawl myself like I wanted to; I had to pay an hourly fee for one of their staff to do it for me, and it was going to take dozens of hours. I debated whether to make this costly investment (out of pocket), but ultimately I felt like it was important enough for the book—and for John Williams history.

So the very friendly Rose at Local 47 took my sweeping request—to comb through every film and television session from 1957 to 1963—and over the course of six months, she gradually updated a spreadsheet with every single credit she could find of our John T. Williams playing piano on a session. There was always the risk that a credit could slip through the cracks of this search, plus the caveat that some reports might simply be missing from the archive, so there was never a guarantee that my list would be totally definitive.

But the credits started piling up, and looking at this ordinary green Google spreadsheet was like looking at a slightly blurry polaroid of John’s life during these six years slowly coming into focus. I knew where he was and which composer he was playing for on any given day, and it was a truly illuminating revelation—rich with new data and potential stories.

The very first film or TV credit the AFM found of John playing a session was for the weirdly titled CBS sitcom, The Gale Storm Show: Oh! Susanna, on April 20, 1956. (He would have been 24 years old.) The composer was Leon Klatzkin. An inauspicious start, for sure, but now I had a pretty reliable idea of where this timeline began.

I was keeping my eyes peeled for specific titles that I’d always heard John had played on. It surprised me when Carousel didn’t pop up on the spreadsheet; it was long believed that John played piano and/or did arrangements on the 1956 Rodgers and Hammerstein musical (which starred his future wife, Barbara). But this was the first of several sad trombone moments—rumored credits that my AFM research debunked—which would [SPOILER ALERT] come to include The Pink Panther, Breakfast at Tiffany’s, and, yes, To Kill a Mockingbird. John did not play on any of these iconic scores.

He did play on lots of B movies and forgotten scores and obscure TV shows. The spreadsheet is littered with unfamiliar titles and composer names, along with some commercials.

There was yet another myth that quickly became exposed. I had always believed that John was the staff pianist in the Columbia Pictures staff orchestra, based on stories he had told about auditioning for their musical director, Morris Stoloff. I knew that the studio orchestras disbanded right around this time and everything went freelance, so I wasn’t sure how long this staff position would have lasted. But I at least expected the first year or two of credits to be dominated by Columbia titles—and yet the spreadsheet revealed this not to be the case.

I was able to ask John about it, and he confirmed that, indeed, he was more like their first-call pianist, a favorite of the contractor Dave Klein. “I was just a freelancer,” he said, “and I had kind of an informal relationship with Klein, and Morris Stoloff, who was very supportive of me.”

It was one of several validations of having undertaken this project: if I hadn’t initiated the records search, I would never have known!

A lot of my discoveries were, admittedly, disappointing. I was hoping to find out that John played piano on one cultural masterpiece after another. But even debunking the rumors was helpful, and every bit of data helped me find the correct piece to construct the jigsaw puzzle of John Williams.

And he did play on some amazing and historic and noteworthy titles! He did, for instance, play piano on the score for Funny Face, the Audrey Hepburn / Fred Astaire picture. His one session—for composer Adolph Deutsch—took place on September 19, 1956. Incredibly, that same day he also played on a session for Dimitri Tiomkin’s Gunfight at the O.K. Corral.

For this post I tried to find clips or scenes from these films that featured piano. It was way harder than I realized, and I can’t even promise that the piano you hear in these clips is John playing—but it’s a fairly good bet. Here’s a kooky piano moment in Funny Face:

The next major title he played on—and his first for Alfred Newman, who would become a mentor and John’s entreé to the entire Newman dynasty—was South Pacific. That session was at Fox on January 1, 1957. (A bizarre movie!)

Pretty quickly John was getting calls to play on scores by A-list composers—like Elmer Bernstein’s The Sweet Smell of Success. Session date: June 3, 1957.

A friend of the Williams family was composer George Duning, who Johnny Sr. had met through playing in the Columbia orchestra. John played both piano (on January 27, 1958) and the Hammond Novachord (January 31, 1958) on Duning’s score for Bell, Book and Candle—the witchy rom-com starring James Stewart and Kim Novak (the same year those two were in Vertigo). As was the case on several sessions, John’s dad was also in the orchestra playing percussion.

In 1959 alone, John played on the scores for Porgy and Bess (André Previn), the Doris Day romp Pillow Talk (Frank De Vol), the Gregory Peck nuclear apocalypse movie On the Beach (Ernest Gold), the Dean Martin drama Career (Franz Waxman), the Oscar-winning Elmer Gantry (Previn again), and Robert Mulligan’s The Rat Race (Elmer Bernstein). He also played piano and did arrangements on Gidget (1959)—earning his own early title credit.

Two superstars crossed when a guy named Jerrald Goldsmith hired John to play on a few of his early pictures. Jerry Goldsmith was a few years older than John and already scoring his own feature films, and the two would become friends and friendly competitors, playing four-hand piano at parties together as well as often vying for the same jobs. And their relationship began on the scoring stage for the Goldsmith-composed noir thriller City of Fear (1958), the sturdy western Face of a Fugitive (1959), and the messy urban drama Studs Lonigan (1960).

Warning: blurry resolution, drunken carousing, Jack Nicholson behaving badly, and an absolutely lethal piano solo.

The starriest, most iconic films that John played on were mostly known. He likes to tell the story of “accompanying” Marilyn Monroe on Some Like it Hot. In reality, he was listening to her pre-recorded vocals through headphones in a studio—but this is him on the keys (recorded in sessions on January 13–15, 1959):

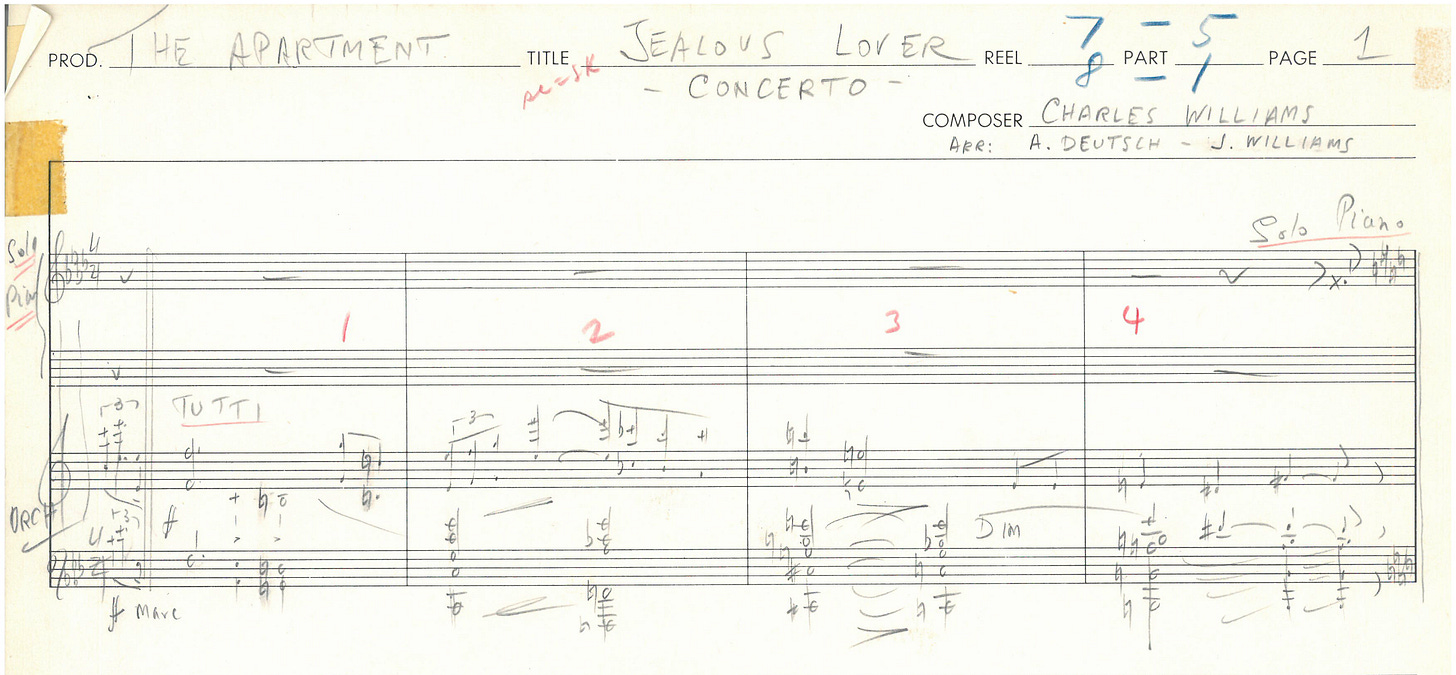

Adolph Deutsch, one of John’s early mentors and patrons, hired John not only to play piano but also do some arranging on the score for Billy Wilder’s The Apartment (1960). The recurring theme in that classic film is the tune “Jealous Lover” by Charles Williams (no relation)—and John, already an expert arranger, did some of the charts. (The Apartment sessions took place throughout April 1960.)

One of the most timeless projects John played on was also the one that basically finished his session career. He was tired of sitting in the studio day after day, playing take after take of sometimes not-very-challenging music. By now he was already scoring his own shows and films—as a contract composer at Universal’s television unit, Revue—and he was ready to get out of the pit. But from June 21, 1960 to August 4, 1961, John played on multiple sessions for the musical film West Side Story.

It was after one of these sessions that he went home and said to Barbara: “I don’t want to play anymore.”

When Rose finished her search through 1963, I gave John a printout of all the credits I had compiled. I think he was a combination of astounded and embarrassed; he did say he thought there were some missing titles, though I never got to find out which specific films he meant.

Sadly, I was unable to find any Bernard Herrmann score credits; I’d always been sure that John played piano for his famous older friend. I asked John about this point blank, though, and he said he never played piano for Herrmann. “I met him on a TV score,” he said, “which I think was Twilight Zone. I wouldn’t swear to it. But it was a night session at RKO, which I remember very clearly—and I remember him.”

But, one of the final—and strangest—sessions John played on for another composer was The Birds. Which was a Herrmann project, technically, but if you know anything about Hitchcock’s 1963 film, it’s that… there is no score. So what was this “solo session (pre-recording)” John did for The Birds on February 21, 1962?

The eureka moment I had was maybe the most thrilling of this whole adventure:

“I did an awful lot of film work, Tim,” John said, in a conversation about his session work, “of all kinds. I mean, good, bad—everything.”

One day he laughed as we were going through the AFM credits, and said: “Is it really good for your writing to be doing all this research?” He quickly added, “If it’s fun, it’s fine.”

It was fun.

Jaw officially dropped. Melanie’s playing in THE BIRDS? I’d buy multiple copies of your book for that fact alone! Thanks for another beautifully written (and dramatic) piece.

This is the period I’ve always been most curious about because it’s presumably where he first started learning many film music idioms, which are often a lot different than concert music and jazz. Thank goodness you’ve been out there grinding away and even personally financing the research Tim! It might have been lost forever. I’m curious, did he ever work on any Leith Stevens scores? I know they were both at Revue at the same time but maybe the relationship started earlier?