On the Trail of: John Williams in the Air Force, and the Studio

From Tucson to Newfoundland to New York—and finally back to Hollywood.

For more context, read Parts 1 and 2 of my On the Trail series.

Living links are extremely exciting when you’re researching a person’s life, especially if that person is as advanced in age as John Williams. You can imagine how many people from the early days, for a man born in 1932, are no longer with us. (I love pointing out to people that John is older than Elvis.) This is true even of figures from his early adulthood; two of the most critical people in his life, who I so wish I could have interviewed, were André Previn and Lionel Newman—both gone.

But as I mentioned in earlier posts, I was able to track down characters from as far back as John’s high school in North Hollywood (though nobody from his childhood in Flushing, unfortunately). And thanks to a composer friend, I got in touch with a man named Bill Peterson—who, in addition to being an accomplished trumpeter and composer and one-time president of the Local 47 musicians union, was also stationed with John Williams at Davis-Monthan Air Force Base in Tucson in 1951, and he had some fun stories of their adventures.

As usual, I don’t want to give away much of what’s in the book—but it was great going over to Bill’s house (he lives here in L.A.) and hearing what John was like as a fresh-faced airman and what his time in the Air Force entailed. John spent a year at Davis-Monthan, playing in the 775th Air Force Band, but also playing jazz with Peterson and two old pals from back home, Mel Pollan and John Bambridge, Jr. (who was a very important figure in John’s early musical life). They would even, occasionally, pile in the car and drive back to L.A.

People still called John “Curly” in the Air Force (that nickname seems to have petered out by the time he was discharged in 1955), and Peterson attested that music continued to be John’s all-consuming obsession while he was in the service, and that he practiced the piano almost around the clock. He told me that all the guys on base liked to throw a ball around in their downtime, except John, and when Peterson asked John why he didn’t want to play catch, “he just held up his finger.” Meaning: John didn’t want to risk messing up the moneymakers.

One thing I learned—and love—is that John has always been an old soul, a man out of time, and that was true as far back as his service days (if not earlier). “John always would wear a coat and tie,” Peterson told me. “Everybody else would come in with a t-shirt or whatever, but John always had a great deal of self-respect, and the knowledge that one should look the part.”

“I just think about that great smile,” Peterson said, thinking back on young John, “and those knowing eyes. It didn’t matter what situation he was in. He was in control, and not being pushy or aggressive—just John.”

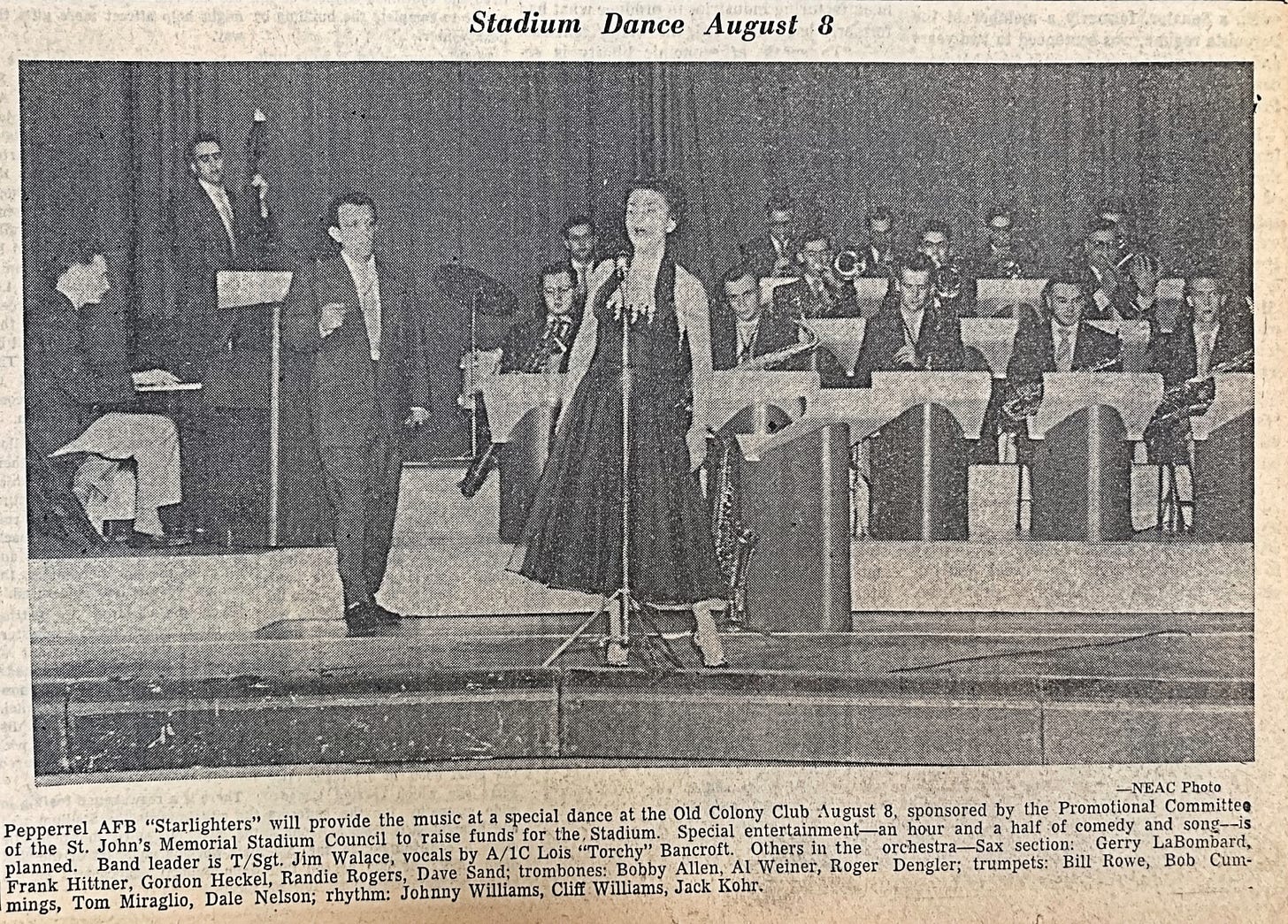

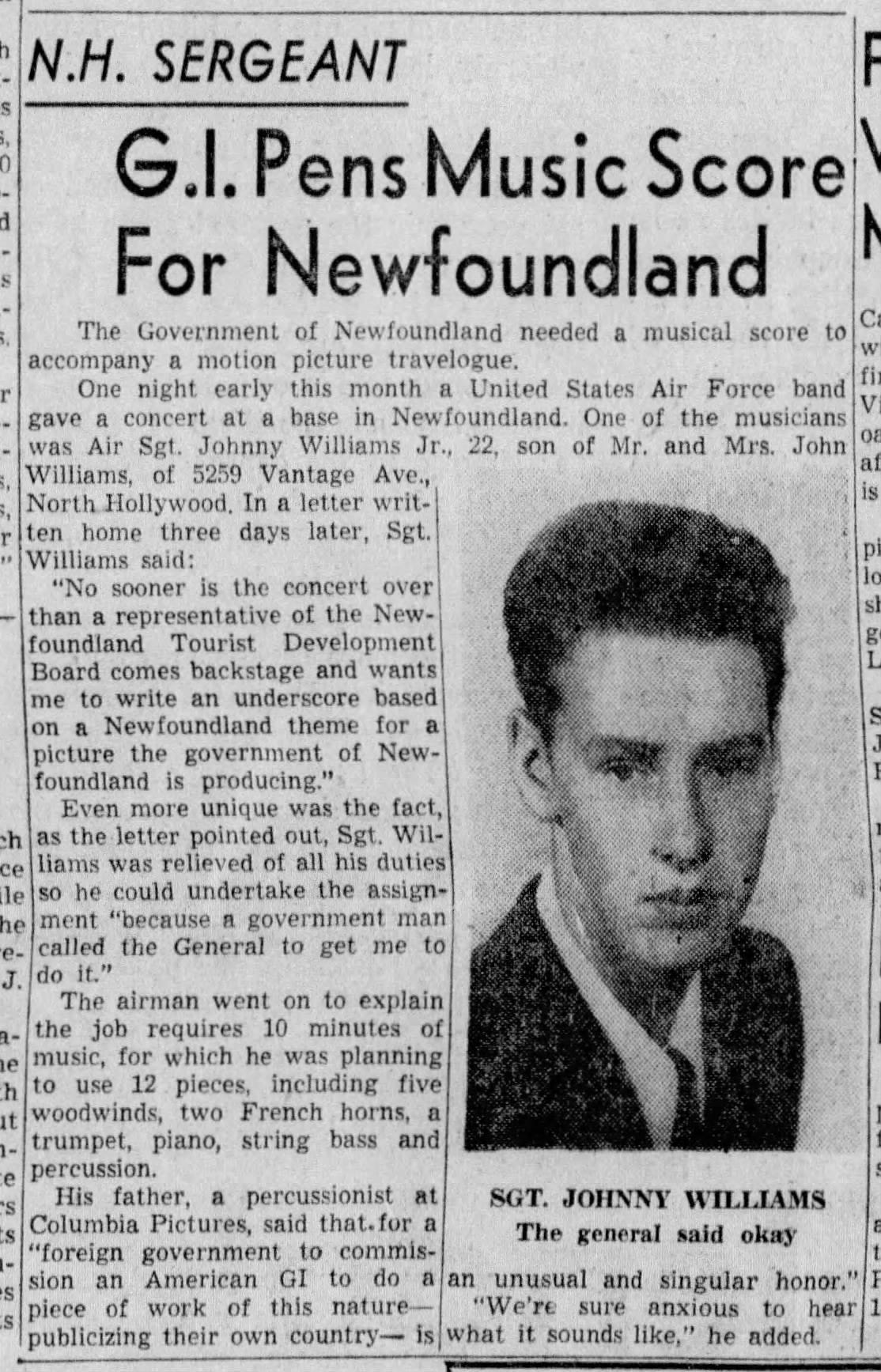

In 1952, John was transferred to St. John’s, Newfoundland, and to Pepperrell Air Force Base—which was an even more significant experience in his life. I found some clippings in local papers about his exploits, and a photo or two, but not a ton of archival information. One of my great allies in this research was a John Williams fan in Germany, Jan Grabowski, who just happened to notice I was “clipping” related articles on Newspapers.com and reached out to see what I was working on. Jan is a great sleuth, and he found lots of articles and information sourced from all manner of deep and obscure pockets of the web that included many bits and pieces that I would have otherwise missed.

A very fun byproduct of this whole experience was making new friends and co-conspirators, and in many different parts of the world. Thank you, Jan!

(I also want to shout out fellow JW cultists Miguel Andrade, Maurizio Caschetto, Thor Haga, and Travis Elder—among others—for providing me with loads of archival materials, answering many questions, and helping me sleuth John’s past.)

John has often recounted the story about John Ford’s The Quiet Man being one of the first films he saw where he really took notice of the score—he sort of winked at this connection when he interpolated Victor Young’s love theme into his score for E.T.—and he saw it while stationed in Newfoundland. I was happy when I found the local ad (which I printed out and shared with him):

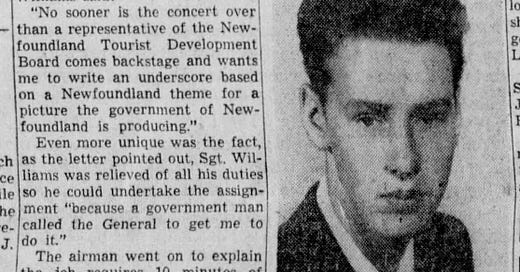

Besides continuing his own self-education as a performer and arranger while surrounded by many world-class musicians, John’s time at Pepperrell is noteworthy because it was where he “scored” his first “film.” You Are Welcome is a clunky little travelogue that our 21-year-old airman was asked to write music for, after members of a German production company heard his arrangements of local folk tunes at an Air Force concert.

John would be the first person to put down his work on You Are Welcome—“It was not an original score,” he has said; “I did not have a clue or an idea on how to do that”—but it is ground zero for his movie composing career, and thankfully someone had the wisdom to preserve it. The short film has been floating around on YouTube for years, and it’s a fun little novelty for us JW nerds.

The bulk of anecdotes and important information I got about John’s experience in the Air Force came from his own lips, once he and I finally started talking, and the book really attempts to flesh out this pivotal era in his life. He had talked some about his Air Force experience in interviews over the years, but I learned so much more through getting to ask him about it in detail. The early chapters of my book were the ones most transformed by my interviewing John at length; I really focused our chats on the first 25 to 30 years of his life, at least initially, because it was the area with the most mystery and historical gaps.

Also, thanks to John (magnanimously) granting me access to his personal photo archive, I was able to see some incredible photos of him during his airman days—some of which are in the book.

John had never been the subject of a documentary when I was working on the book—but that didn’t mean he had never participated in documentaries. He had, in fact, given interviews for several of them, on various subjects, and these proved to be a goldmine… especially when I was able to obtain the full conversations that the various directors recorded with him.

For instance: in researching the time, after he left the Air Force, that John spent studying with the legendary Juilliard teacher Rosina Lhévinne in New York, I was able to get my hands on a filmed interview that John gave for a documentary about Juilliard where he talked all about Lhévinne and that time in his life—which was a brief but essential piece of his formation. He also gave interviews for documentaries about the singer Frankie Laine, the lyricist Johnny Mercer, the Sherman Brothers, as well as ones about film projects he worked on (Fiddler on the Roof, etc.), and even an un-produced documentary about Alfred Newman. Many of these filmmakers were generous enough to share John’s complete interviews with me, and I found so many gems and leads in these deep dives off the beaten paths of Spielberg and Star Wars. (Having said that, one of the great sources of unique anecdotes and amazing footage is a well-known 1980 BBC doc that was timed to the release of The Empire Strikes Back.)

These raw filmed interviews were also opportunities for the very grown-up, sophisticated, and scholarly work of… making gifs. I especially love this one, taken from the Frankie Laine doc, where John’s patience is wearing a bit thin:

After his time with Lhévinne, John returned home to Hollywood to start a family—and his career.

It was truly remarkable that I found audio and film recordings of John as a child and in high school, but now I was finally getting into the period of his life where he was frequently in a studio and making industry news as a budding recording artist. I initially did my best to try and nail down every pop or jazz album that John played piano on, but in the end I realized I just couldn’t devote the time or energy to compiling a definitive list—especially knowing that I would only be summarizing this portion of his story in the book, and that I likely wouldn’t have the space to include lengthy appendices and discographies. (John was undoubtedly happy about this; remember that, when I brought in a stack of his old LPs, he called it schadenfreude.)

Thankfully, the internet has a ton of information about old recordings—on sites like Discogs, which also has scans of vinyl album covers and inserts with liner notes and credits—and also many John Williams detectives have been working on this particular beat since well before my efforts. I do hope that, one day, there will be an authoritative, exhaustive list of all his studio credits. But alas, not in my book. (Maybe the second edition?)

One comprehensive list I did want to invest in making was every single film and TV scoring session that John played piano on. I imagined including this as an appendix in the book, and I was excited to finally confirm (or debunk) the many rumored scores John supposedly played on (To Kill a Mockingbird, West Side Story, etc.), and uncover a thousand others… and, hopefully, some really cool ones.

The findings were both enlightening, myth-busting, fascinating, a little disappointing—and extremely expensive! This fun slice of John’s life will be the subject of next week’s post.

You may have noticed the spiffy new artwork for Behind the Moon. It was all designed by the inimitable Jim Titus, maestro of soundtrack album art (and particularly all of La-La Land’s great archival releases of JW’s music). I literally couldn’t have asked anyone better to do it. Thank you Jim!

Thank you so much, Tim. It has been a true pleasure for me to research hidden clues and bits about John's early years and to support you and your book with the details. Anytime again:-)

John Williams' time in High School and in the Air Force as well as his early years in the studio during the 1950s & 60s have always fascinated me, and it is a great fortune that you had the opportunity to talk extensively with John about this phase of his life and also to hear some anecdotes from other companions, like Bill Peterson. This fills in important gaps that would no longer be possible in this form in a few years.

It is wonderful that you share so many personal stories about the creation of the book in the series 'Behind the Moon' with us, as well as giving insights into your collaboration with John and the biography. The anticipation for the book release is thus increasing weekly!

I know I haven't even got my hands in the first edition yet, but I'd buy a second edition including an authoritative, exhaustive list of all of Williams' studio credits in a heartbeat!

I'm *really* excited about next week's post!