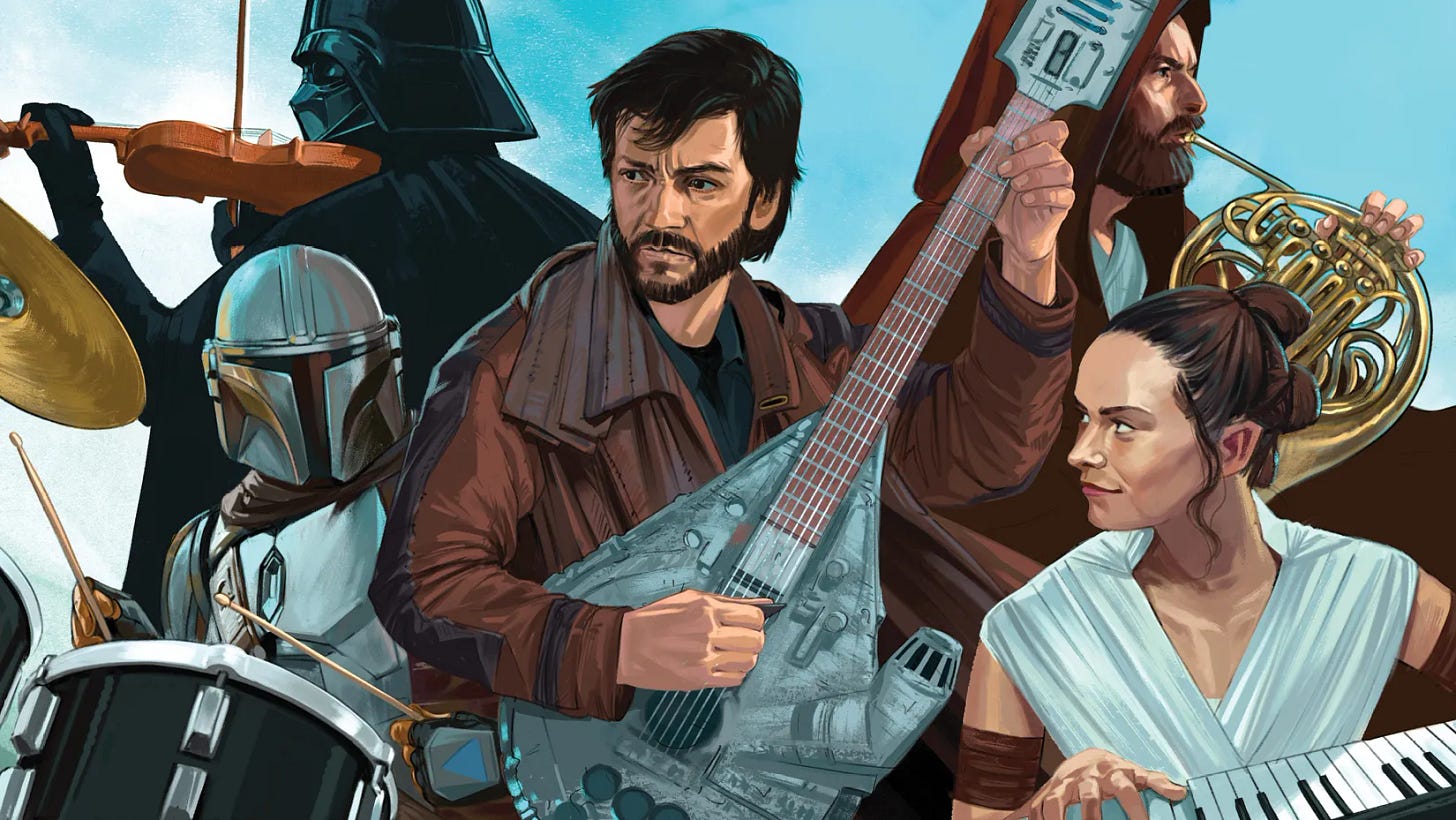

Star Wars: a musical evolution

A recent Hollywood Reporter assignment has me thinking about the musical bible that John Williams wrote for Star Wars... and how it's been reverently, and irreverently, treated over the years.

Happy Andor Day!

The Hollywood Reporter recently hired me to write an article for their April 16th magazine, about the ways in which “Star Wars music” has evolved over the years; it was prompted by the use of a Steve Earle rock song in the trailer for Andor season 2 (which drops today on Disney+), and it was very fun to write.

My piece is free to read online, and it has already sparked some lively debate among film music fans, most of whom seem to feel that any attempt to deviate from the John Williams “style” in the feature films he scored is pure sacrilege. The article was intentionally not a piece of criticism, mostly just fun reportage and interviews, and I didn’t make a lot of value judgments in it—although my high opinion of both Ludwig Göransson’s music for The Mandalorian and Nicholas Britell’s score for Andor (season one) wasn’t at all hidden.

I got excited when I started plotting out what all I could include in the piece, which could have easily been four times longer, but word count restraint meant that I could only skim the surface…

Thankfully, I have my own John Williams themed publication where I can put all of that frustrated energy!

As an obvious John Williams cult member, I don’t have to tell you that I consider his music sacred. But do I consider Star Wars sacrosanct? Not at all. I have deep affection and nostalgia for the original trilogy, although my feelings about those movies have evolved over time and I have a pretty clear (critical) head about their many shortcomings and childlike simplicity. The prequels I have way less affection for, and consider them all extremely flawed and largely downright bad. The Disney sequel trilogy, while boasting some gorgeous photography and cool effects and touching moments, I mostly despise. I could not care less about the spinoff books, the cartoon series, the Ewok movies, etc., etc. I got pretty tired of Star Wars pretty quickly, so it’s actually kind of a miracle that I really liked the first two seasons of The Mandalorian (they had me at Werner Herzog); I also consider Andor (season one) the greatest piece of Star Wars writing and drama… ever. How’s that for sacrilege?

Musically speaking, I love the way Göransson took certain John Williams hallmarks (thematic idioms, orchestration) but then took the music to another place. Conceptually, that’s exactly the same as how John took ingredients from Holst and Stravinsky and Prokofiev to a new place in the original 1977 score and its sequels. Ludwig is, like John, a jazzer at heart, and I think they have a similar gift for absorbing someone else’s musical style and then improvising on it into a new, more personal energy and force. Britell has similar gifts; like John, he is a classical pianist at heart, but he came up in the world of hip-hop and the great film music of the ’70s and ’80s, and he has found a remarkable way to hybridize tuneful, neoclassical orchestra writing with a more contemporary, electronic attitude. I love their music—for Star Wars and Succession and Sinners alike.

(If you’re interested, check out my recent profile of Ludwig and Ryan Coogler for the L.A. Times.)

But let’s set my personal opinions aside for a moment, and just acknowledge that composers and musicians have been monkeying with Star Wars music since Day 1, to all kinds of varying success. From trendy cash-grabs to irreverent parodies to slavish imitation to creatively fresh innovation, there is nothing new about composers having fun with this galaxy’s musicality. And since there is nothing anyone can actually do to tarnish the great work that John Williams did across his nine films (and, to a lesser extent, his themes for spinoffs and Galaxy’s Edge), there is no actual heresy or harm being done by these folks… and some of it’s pretty fun!

It all started a long time ago, in July 1977, in the immediate wake of Star Wars’ galaxy-disrupting phenomenon. The Summer of Star Wars, as John’s double LP was selling like hotcakes and quickly becoming the best-selling non-pop album of all time, inspired all manner of enterprising capitalists to cash in on the craze. And in 1977 that meant one thing: disco. It was actually a very common trend to disco-fy movie themes in the late ’70s (a topic for a future Substack post), and the catchy, almost instantly and globally known tunes from Star Wars were no-brainers.

The first act to get funky with John’s theme, replete with excess wockachicka, was Ernie Freeman and the Graffiti Orchestra.

But the more famous Saturday night fever-heater to boogaloo John’s themes was Meco—aka Domenico Monardo, a nerdy trombonist from Pennsylvania. Meco’s 15-minute dancey collage of themes from the Star Wars score, namely the main theme and “Cantina Band,” was released as a single in July; it sold 2 million copies and sat at the top of the Billboard chart for two weeks.

The next stage of “evolution” was arguably the most sacrilegious, yet done with George Lucas’ authority and featuring all of the original cast (albeit looking like they wanted to be mercifully crushed in a garbage compactor). The Star Wars Holiday Special, which aired on CBS in November 1978, was 97 minutes of risible, embarrassing slop, and it culminated with Carrie Fisher singing an earnest “Life Day” song adapted from John’s main theme (though definitely not adapted by him).

(Hey, at least she did it with sincerity!)

This should be obvious by now, but from the very beginning there was nothing sacred about “Star Wars music.” What John composed for the original films was an incredible trio of modern symphonies—indelible leitmotifs that magically branded each major character (and that you could hum!), swinging action ballets, tone paintings of mystery and atmosphere, elegant musical drama and narration, all developed into a perfectly logical and cohesive musical work while simultaneously supporting, and in fact critically propping up, the (often chintzy) script and the visual storytelling. It was an undeniable, immortal achievement, and John Williams defined Star Wars—whatever “Star Wars” is—as much as any single person other than George Lucas.

And insofar as John felt increasingly protective of his music for these films, insisted on continuing his nine-cycle space opera well past the point where they were worthy of his talents—and insofar as he has been unhappy with the way some composers have adapted (or vandalized) his tunes—it is sacred.

But let’s keep going, heretics!

A much cooler and more musically intriguing adaptation occurred in the summer of 1980. The Empire Strikes Back was far and away the biggest hit of the year, another global phenomenon, and as per usual Meco hopped on the gravy train and released a disco medley of themes; Boris Midney, a Soviet defector from the Moscow Symphony Orchestra, also released an electronic disco album of its themes.

But the most unusual, and impressive, ancillary to John’s new opus was Empire Jazz. Robert Stigwood, a tycoon of ’70s pop culture, was the Australian manager of the Bee Gees and founder of RSO Records, which claimed the blockbuster soundtrack album for Saturday Night Fever (a film Stigwood also produced). RSO put out the official 2-LP album for Empire as well as the Midney album, and Stigwood had the off-the-wall idea of approaching bassist Ron Carter to make a jazz album based on the score’s major themes. A Detroit native and Manhattan School of Music graduate, Carter had played with Miles Davis and many other legends, and is considered perhaps the most important bass player in jazz history.

“Williams told me he knew my name and reputation, and trusted me when I told him I wanted to change the timing of the songs from 4/4 to 3/4,” says Carter, who had been aware of John’s own jazz reputation back in the day (and who I interviewed for my book). He didn’t actually see the film before setting to work, but “I had the melodies; they were descriptive by themselves. Seeing the picture wouldn’t have been critical to making it work.”

One of Fox’s stipulations for the album was that the cover—an illustration of a smoke-filled jazz club with Chewbacca on the keys, C-3PO on bass, and a Stormtrooper on sax, with Darth Vader seated in the audience—couldn’t show the droids holding any kind of alcoholic drink. “I said, ‘Well, I can do that,’” Carter recalls. “I mean, I don’t drink, and I don’t know any robots in my neighborhood.”

RSO gave Carter a small budget, and he hired some of his most talented friends—among them Bob James on piano, Hubert Laws on flute, Jon Faddis and Joe Shepley on trumpet and flugelhorn, and Ralph McDonald on percussion. “A really good band,” says Carter. John’s team sent over sketches of his new main themes—“The Imperial March,” “The Asteroid Field,” “Han Solo and the Princess,” “Lando’s Palace,” and “Yoda’s Theme.” “None of them had the complete melody,” Carter explains. “They were just sketches.”

Carter responded most to the ballad for Yoda: “That was the most melodic melody of them all. The other things were like demonstrations of power”—he says, humming the Imperial March:

The themes from this movie, they were all like powerhouse themes, you know, kind of sounds and splashes. I enjoyed the emotions that they presented on the screen. To make a record of that kind of impact is a little more complicated, because you don’t have the visual to go with the impact of the melody. So I tried to write melodies that were a little less over the top, energetically—but they had some motion involved. There was clearly an effort to get this kind of surf going.

In the ballads, I just kind of slowed things down a little bit more than the movie did, ’cause I had plenty of time with these guys in the band, and I thought the melodies could tolerate a little slower pace—because they were melodies with no visual thing involved. It was all about sensing rather than actually seeing on the screen that you should feel this way because the band’s getting louder, and the rhythm’s getting more complicated, and action is heating up on the screen. All I had was a score and these six or seven guys who were gonna help me get this image across without the visual impact.

Carter and his merry band went into the Aura Recording studio in New York City at 11am on a Monday, and by 8pm Tuesday the master tape was in RSO’s hands. “I saw the movie a couple of weeks later,” Carter says, “and I was very pleased, especially with my version of Yoda’s theme. I think I captured the vision of Yoda.” In his four-star review for the LA Times, famed jazz critic Leonard Feather called the album a “surprisingly authentic set.”

Carter never performed these jazz arrangements live; RSO Records was absorbed by Polygram and Empire Jazz went out of print. “I keep hoping that when the next episode of Star Wars comes out, I will have found out by then who’s in charge of this music,” Carter told me in 2021. (He’ll turn 88 on May 4.) “I never found anyone to talk about that, so it continues to languish here. Someday it’ll get done, but I’m not sure I’ll be around to see that.”

As a half-baked record producer myself, I tried to crack this nut—but after doing some digging with the help of a veteran archival producer, I found that the rights to Empire Jazz are owned by Universal Music Group (which purchased Polygram), and they have no interest in reissuing it themselves or licensing it to a specialty label. Alas. I was at least able to find a copy of the LP, in mint condition, at the amazing Record Collector in West Hollywood—and the whole thing is also up on YouTube.

In my Hollywood Reporter piece, I noted how Lucas considered hiring the band Toto to write a song for Return of the Jedi. I was incorrect when I wrote that it would have been for the finale celebration; it was actually for the live (puppet) performance inside Jabba’s palace. “It was hard to do,” Lucas said at the time. “We’d contemplated bringing in rock & roll composers to try their hand; we talked to Toto at one point and a few other groups and writers to see if we could come up with something very bizarre or unique. But we didn’t want something too Top Forty; we wanted something strange but lively. It was a similar situation for the end music. We had endless amounts of overlays, various types of Ewoks singing, various instruments, and it sort of evolved from a gospel/rock-n-roll thing to the much more primitive thing that it is now. In both cases, it was a mater of weighing the ethnic realities with something musically interesting.”

Even within these films, within the ecclesiastical canon, Lucas was totally fine with getting experimental—and getting funky. John had already established an in-world genre of bebop with his Cantina Band music; for Jedi he wrote “Jabba’s Baroque Recital,” a fairly normal piece of baroque source music for a very abnormal setting, and “Lapti Nek,” the funkadelic ditty sung by Sy Snootles and Max Rebo’s straight up FIRE band (which Lucas regrettably classified as “jizz”). #maxrebocoachella2026

(RIP Oola.)

Then, in 1997, Lucas replaced “Lapti Nek” with “Jedi Rocks,” an abhorrent ska song composed by Jerry Hey; and he replaced “Yub Nub” with a new, more dignified finale piece that John composed.

You see how I mean this topic could be four times longer than my HR article? Are we still having fun?

—

I started thinking about all the various spinoffs and ancillary properties, the “satellites” to the feature films in the Star Wars galaxy. You had, of course, Atari and early Nintendo games in the 1980s, which mostly adapted John’s themes for 8 bits.

I can’t go very deep on the games, for the simple fact that I don’t play them. I did play X-Wing and TIE Fighter for PC when I was a kid, but the latest Star Wars games I ever messed with were Jedi Knight: Dark Forces II (which I often played remotely with my friend Trevor on a dial-up modem) and The Phantom Menace tie-in game for Windows. Those were cool, and they all used John’s themes from the films—and even the actual recordings—quite faithfully. I know the game universe has expanded radically in the past 25 years, and that it contains both original scores lovingly written in John’s style as well as some eclectic departures.

I confess that I never played Shadows of the Empire, the 1996 shooter game that was scored by Joel McNeely in a pretty straightforward imitation of John’s voice. I have almost no familiarity with that score, although I know it has many fans. But this brings up an interesting paradox; I typically don’t like it when a composer tries to write a blatantly John Williamsian score. I’ve discovered that a lot of JW fans are only interested in adaptations that try to reverently emulate his sound—grand and orchestral and “Star Warsian.” I’m not opposed to this as a principle; I’m just not that interested in copycat scores, whether it’s Shadows of the Empire or Jurassic Park III. As talented as the forgers may be, there’s just something phony and hollow to me about a score, written by someone who isn’t John, trying so hard to pretend it was written by John.

Which is partly what makes me way more open to the work of Göransson and Britell, who have gone in uniquely fresh directions while still keeping a toe in the Williams world. I genuinely feel like the brassy theme for The Mandalorian sounds like a great lost Williams theme (maybe closest in character to “Parade of the Slave Children” from Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom), while also having a complete personality of its own, with the awesome inclusion of bass recorders, synths, fuzzy guitar, and sampled boot spurs.

Both Göransson and Britell are talented orchestrators with a deep love of classical traditions as well as classic film music, and both have a knack for lyrical melody. But they also both have hip-hop and electronic bonafides, lean towards minimalism, and are conversant with pockets of modern pop music and non-western idioms that John is not (neither for better or worse), and they brought all of that to bear in their very special and effective scoring for Mandalorian and Andor, two shows with vibrant and particular musical personalities. I truly love it.

I confess I have not spent any time with the music of Kevin Kiner for The Clone Wars and his other animated series—although, funnily enough, Kiner was the very first film/TV composer I ever interviewed, for Film Score Monthly, back in August 2008. I must have seen the Clone Wars film in preparation for that phone call? I have no memory of it.

The ridiculous proliferation of Star Wars shows, movies, games, and Disney lands in this Disney Era is both too much to keep up with and of way too little interest to me. I did not like Rogue One as a movie; aspects of the Michael Giacchino score are nice, but I know it was created under extremely chaotic conditions and it’s awkwardly caught in between a space rock and a hard place trying to cosplay as authentic John Williams. I didn’t like Solo either, although I think what John Powell wrote was really good, and a nice template for how to honor the Williams idiom while still being true to the new composer’s own personality and style. The Book of Boba Fett was terrible; Ahsoka was ah-SO not for me; Obi-Wan Kenobi should have been a movie (or just not existed); The Acolyte was, pardon my Huttese, straight up bantha poodoo. Although the latter was an instance of a very classically talented composer, Michael Abels, (often) doing an ace imitation of John Williams’ voice in a way that did not bother me at all. I just wish the show had been worthy of his talents.

So what have we learned here? (Other than that I had way too much time on my hands this week.) I ended my Hollywood Reporter piece with a fun quote from my interview with Steven Gizicki, a music supervisor who ran the music department at Lucasfilm when Lucas was still at the helm. “‘Jedi Rocks.’ Enough said.” Basically my point was that “Star Wars music” has always been eclectic, has always been a wildly big tent, has always been a mess. Just as Star Wars itself is a huge, eclectic, unwieldy mess. If anything, the “franchise” (and I so hate that art-hating word) has proven that it can contain everything from bebop to funk to disco to jazz to electronica to, of course, John Williams’ orchestral majesty. And as much as I simply don’t care about most of the further and side adventures in the galaxy far, far away, and as much as I worship the musical liturgy of John Williams, I contend that the only way to keep Star Wars interesting is by giving new composers free rein to imagine their own particular path through it—away from the canonized past and into the unsettled future.

I couldn’t agree with you more. The faux-Williams scores have always left me cold, while the music of THE MANDALORIAN and ANDOR reflected the freshness of their stories and characters. Thanks for another great piece, and one that proves with succinctness and wit that you will never run out of compelling John Williams topics to write about!

Excellent piece! Thank you for both this and the HR piece. I think you have the healthiest view of Star Wars music (and the entire franchise) of anyone I've read in the last fifteen years. Basically, let it be what it's going to be. Yeah, some of it's going to downright suck. But we don't get Andor without suffering a couple from the other side of the spectrum.

I adore that you included "Empire Jazz." For me, that album came along as my appreciation and study of jazz was starting to grow, and the idea of adapting such well loved themes in that way opened up the world of jazz arranging to me at a very early age.

I do have to add two items to your list, though. I think the score that Stephen Barton and Gordy Haab created for "Jedi Survivor" is a fantastic piece of writing that probably sits alongside John Powell's "Solo" as a way to maintain a unique voice while honoring the spirit and sound of what John created.

I also can't believe you left out The Electric Moog Orchestra! I wore out two 8track (that's right kids, 8track) tapes of that version in my dad's car.

It's always a joy to read your work. Thank you from a fellow cult member.